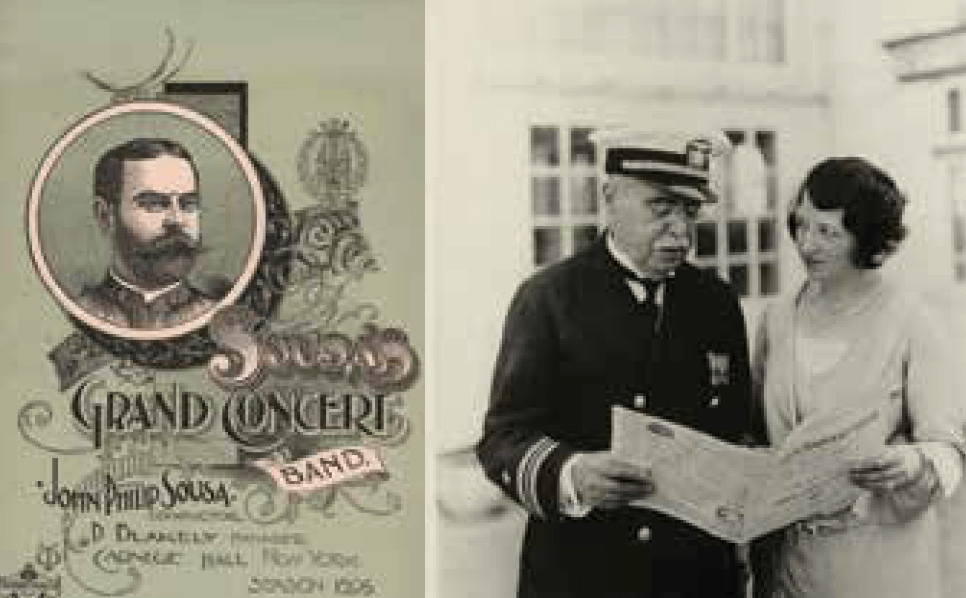

The world-famous John Philip Sousa Band featured a soprano soloist in many of their concerts. Like his instrumentalists, his vocalists were the best in the world.

The world-famous John Philip Sousa Band featured a soprano soloist in many of their concerts. Like his instrumentalists, his vocalists were the best in the world.

Sousa referred to them individually as, “The Lady in White,” which was his general term for any of his female vocal soloists.

The Lady in White changed throughout the years, but all had common qualities. To be a soprano soloist in the Sousa Band, the vocalists not only exhibited superior talent, but they possessed beauty and stage presence, as well. They were all polished artists and had strong voices which could fill any concert hall in which they were to sing.

To provide focus on the soloist, Sousa wisely “waved out” certain instrumental players to reduce the quantity of brass, never to drown-out his soloists. At these times, his arrangements were never written for full band, but concentrated on woodwinds; clarinets especially. He also included the harp, and, in brass, the horns and the bass. Percussion was often limited to timpani.

The Sousa Band performed over fifteen thousand concerts in their existence from 1892 to Sousa’s death in 1932 and featured over forty female sopranos in that length of time. “The Lady in White” were all women who enjoyed a variety of interesting lives and careers before and after singing with Sousa. Each had their own story.

Estelle Liebling (1880-1970) sang over sixteen hundred soprano solos with the Sousa Band, and never missed a performance. Liebling came from a musical family. Her father, Max Liebling, and his brothers, Emil, George, and Solly, all studied with Franz Liszt. Her brother, Leonard, was the editor-in-chief of the Music Currier.

Estelle was only eighteen years old when she made her debut at the Dresden Royal Opera House in the title roll in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. She studied in Berlin with Selma Nicklass-Kempner, and in Paris with Mathilde Marchesi.

She would go on to coach or train about eighty New York Metropolitan Opera singers. Among her students were Amelita Galli-Curci, Frieda Hempel, Gertrude Lawrence, Jessica Dragonette, and Adele Astaire. Astaire was the sister of dancer, Fred Astaire.

She also taught Kitty Carlisle, a great supporter of the arts. But her most famous student was a daughter of an insurance salesman in Brooklyn, NY. Her friends called her Bubbles, but her real name was Belle Miriam Silverman. The rest of the world would come to know her as Beverly Sills.

Another soprano soloist with the Sousa Band was Marcella Lindh (1867-1966). Lindh, who was born, Rose Jacobson Jellinek, was the daughter of German Jewish immigrants, and sang with Sousa from 1892 to 1894. Marcella studied in Berlin and was the first woman to sing solos after Sousa formed his own band. Among other engagements, she sang with Sousa at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1893.

Lindh also sang with the New York Symphony under Walter Damrosch, and at the Metropolitan Opera House. She relocated to Budapest where she taught at a conservatory. She returned to the United States, to her native Michigan, where she remained the rest of her life.

Virginia Root (April 14, 1884-June 2, 1980) sang with the Sousa Band from 1909 to 1917. Virginia, whose real first name was Eleanor, also had musicians in her family tree. She was the great-niece of American composer George Frederick Root (1820-1895), who published over five-hundred pieces of music. Among his works were The Vacant Chair (We Shall Meet But We Shall Miss Him) (1861), The Battle Cry of Freedom (1862), Just Before the Battle, Mother (1864), and Tramp! Tramp! Tramp! (1864).

Virginia Root was with the Sousa Band on their around the world tour in 1910-11. After Sousa, Root sang with the National Opera Company in New York and various symphony orchestras. She resided in Scarsdale, NY and died in Springfield on June 2, 1980.

Mary Baker, of Brooklyn, NY, sang with Sousa from 1919 to 1922. This coloratura soprano was discovered by Sousa when he was the guest of honor at a musical produced by the Mundell Choral Club of Brooklyn. Baker sang the aria from David’s Pearl of Brazil, with flute obbligato, and Sousa hired her before they were even introduced! Her first tour with the Sousa Band began on June 14 and closed on September 1, 1919. Baker was a pupil of M. Louise Mundell, who was the director of the Mundell Choral Club.

When Baker dazzled Sousa audiences with her rendition of The Wren, by Benedict, the flute obbligato was played by a young member of Sousa’s Band named Robert M. Willson. Willson was better known by his middle name, Meredith, and would later write such Broadway musicals as The Music Man, and its signature song, Seventy-Six Trombones. Besides accompanying Baker, Meredith Willson left Sousa in 1923 and from 1924 to 1929 played in the New York Philharmonic under Arturo Toscanini.

Baker also sang Hallett Gilberte’s waltz song, published by Presser and Co. in 1916, Moonlight-Starlight when on tour with Sousa, demonstrating she sang both old and new songs.

Other numbers Baker sang on Sousa’s Transcontinental Tour included: Carmena by Wilson, I Have Watched the Stars at Night by Fleigier, and Sousa’s own, The Crystal Lute. She also sang an aria from Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, and a selection from Charpentier’s Louise.

Among her encores were Carry Me Back to Ole Virginny. Florence Myrta French sang in the 1896, January to July transcontinental tour. She sang with the Sousa Band in most concerts from 1893 to 1898. By September, 1895, she was represented as one of the artists by the H. M. Hirschberg Musical Agency, of 5th Avenue, New York.

She had gained a reputation as the “Wisconsin Nightingale,” because she hailed from Eau Claire, before she went to New York to study. Realizing she also needed to study in France, she traveled to Marchesi, where she spent two years, and was prepared by Giovanni Sbriglia (1829-1916). After a short tour with Sbriglia, she returned to the United States.

Myrta French, as she was known, was prima donna of the Heinrich Opera Company which performed at the Grand Opera House in Minneapolis, MN in September, 1895, to a, “most appreciative audience.” French had sung successful engagements with both the Damrosch and Seidl orchestras. She appeared in Baltimore in the grand opera, Romeo and Juliet, where she was acclaimed as, “ideal,” and with a, “lovely voice and charming presence.”

After Sousa her career took another direction. She was singing in church events and advertised in the Music Currier as a prima donna soprano, available for concerts, oratorio, recitals, and concert direction, and was managed by music critic and lawyer, Remington Squire, 125 East 24th Street, NY, son of former governor of New York, Watson C. Squire, and Ida Remington, daughter of the Remington Arms Company founder.

French married Jean Paul Kursteiner (July 8, 1864, NY-March 19, 1943, Los Angeles, California) in Eau Claire, Wisconsin on July 21, 1901. Jean Paul, a professor of music, was in his early thirties, and living with his parents, in Englewood, New Jersey. August was born in Switzerland, had immigrated to the United States in 1851, and was a teacher of collegiate courses, and the family must have been financially secure. They had two black servants and a white nurse living in their household.

Kursteiner was born in New York, studied composition and piano in Leipzig, and was quite successful. He returned to New York in 1893, and was appointed to the music faculty of the prestigious Ogontz School for Young Ladies in Philadelphia, and held that position until 1930. He also created and directed a program of piano study at The Baldwin School in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, founded by Florence Baldwin in 1888. President William Howard Taft’s daughter, Helen attended there during his tenure. He also founded the music publishing house, Kursteiner and Rice, in New York, circa 1911, which published his many compositions.

In 1919, the couple resided at 2508 Broadway in New York, and in 1938, the Kursteiners relocated to Los Angeles. Lucille Jocelyn of New York, sang May 30, 1902 at Willow Grove Park, and on the 1902 tour.

Jocelyn was in cast of Eugene Tompkins’ company in the production of Pinafore as Josephine in May of 1894.

Before she was with Sousa, she was an artistic pupil of Francis Stuart, and was noted for her remarkable breath control, and her finished and refined style. She had sung at the Woman’s Philharmonic Society Concert at Carnegie Hall. Around this same time period, she performed two of English composer, Edward Jakobowski’s lullabies, as vocal solos with piano, on Columbia Records.

Nora Fauchald (1898-1971), who was known as the “Norwegian Nightingale” sang soprano solos with the Sousa Band from 1923 to 1927. She was born in Norway, immigrated to the United States, and grew up in North Dakota. She was the daughter of Julius Nelson Fauchald (1866-1937) and Inga Marie Nerseth (1865-1938). They immigrated to the United States in the spring of 1887. Nora returned to Norway in 1913-14, before returning to the United States. In 1921, she resided at 928 84th Street in Brooklyn.

She was a graduate of the Institute of Musical Arts, which became Julliard School of Music, and later, returned to teach there for twelve years. She also taught voice at St. Margaret’s School in Waterbury, Connecticut.

She was married to George Morgan, director of music for the Taft School, for more than forty years. She died at age seventy-three, and resided at Watertown, Connecticut.

Frances Millett Hoyt (1868, New York), soprano, and Grace Hoyt (1873, New York), mezzo-soprano, sang a vocal duet by Edward German, Come to Arcade, from the light opera, Merrie England, Didsbury Theatre in Walden, December 13, 1909, also at the Hippodrome in New York the night before. They also toured with Sousa in 1909.

Before they had sang with Sousa, for example, in 1907, they did what The Music Currier referred to as an “annual matinee musical” in costume, and was patronized by some wealthy and well known people in the New York area. This event was held in the Astor Gallery in New York.

While it is not revealed, it is possible, that through this type event, the Hoyt sisters might have come to Sousa’s attention. Marjorie Moody (1896, Massachusetts -1974, New York) sang over twenty-five hundred soprano solos with Sousa and His Band. She joined the band in 1916, and remained until 1931. She was discovered by Frank Simon, who was a cornet player in the band.

Simon stayed overnight at the residence of Sousa Band clarinet player, Sam Harris. To save on money, when the band was on tour, it was not uncommon for the band members to get a hotel room together, or stay with one another, so Harris had invited Simon to stay with him at his rooming house at 154 Lewis Street, in Lynn, Massachusetts operated by two elderly ladies.

The next morning, the two men were awakened by what Simon thought was, “one of the most beautiful coloratura voices,” that he had ever heard. The sound was emanating from the studio of the spinster lady, Amy Calister Balch (c1868-Sept, 1955), daughter of Melvin and Ada Balch, who, with her elderly, widowed, aunt, Calista M. Piccioli operated the rooming house, and taught music to supplement their income. The voice was that of their star pupil, Marjorie Moody. While Balch focused on teaching piano, Piccioli was well qualified to teach voice.

Moody’s teachers were quite experienced. Piccioli, who was born, Calista Marie Huntley (April 11,1841-Feb 6, 1929), in Marlow, New Hampshire, had studied and sung in Italy under the stage name, Marie Calisto.

Frank Simon, with Harris in tow, immediately invited young, Marjorie Moody to audition before Sousa. Moody sang two of her favorites, One Fine Day, from Madam Butterfly, and an aria from La Traviata. At Simon’s request, she also sang Sousa’s own composition, The Card Song.

Sousa was captivated, hired her, and had her start immediately. Among other comments, Sousa declared, “Young lady, you have a most remarkable teacher.” Over the years, Marjorie Moody earned and enjoyed a special level of trust and loyalty with Sousa. She would sign as a witness to the signatures on several of Sousa’s contracts with the Sam Fox Publishing Company to publish some of his marches. Sousa dedicated two songs to her. One was written in 1926, entitled, There’s a Merry Brown Thrush, and one in 1928, which he named, Love’s Radiant Hour. Moody would sing all over the world, and with many symphony orchestras in the United States.

She was a member of the Sousa Band Fraternal Society. The Lady in White, who sang a soprano solo, was always a feature at any Sousa concert. But on two occasions, at the Hippodrome in New York, the audience, and Sousa, received more than they expected from two sopranos, who were not part of Sousa’s regular band soloists.

The soprano soloist on December 12, 1915, Emmy Destinn (1878-1930), the Bohemian soprano, who, after her final number, appeared on stage, accompanied by William G. Stewart of the Hippodrome staff, who announced Destinn had been re-engaged to fill out the remaining season of Elsa in Lohengrin at the Metropolitan Opera Company in New York.

Upon hearing the news, the volume of her applause doubled, and the audience demanded more; possibly a comment. The obviously thrilled, Destinn, a singer, not a speechmaker, was not prepared for words, but she had to do something. So, she ran over to the podium on which Sousa was standing in front of his band, grabbed his hand, pulled him closer, and began kissing him, “joyously, somewhere in the north-eastern corner of his beard.”

The audience loved it as the grinning prima donna flitted from the stage, leaving a startled Sousa behind.

Unaccustomed to such familiarity from performers (which is commonplace now), Sousa dropped his eyeglasses, momentarily lost his balance, and risked losing his composure, while the applause thundered on. But the usually unflappable Sousa, soon regained all three, and continued an unbeatable performance when the applause finally ceased.

About 30 days later, on January 9, 1916, also at the Hippodrome, Sousa was again the startled recipient of another unexpected kiss by a prima donna; the diminutive Japanese soprano, Tamaki Miura (1884-1946). After singing her feature number, The Last Rose of Summer, the Japanese soloist, ran over, pounced on Sousa, and planted a big kiss on his beard, which was as high on Sousa as she could reach.

This time, Sousa responded with a quip, which referenced the Great War, (later known as World War One) which was then raging, and involved the countries from which the two sopranos were born. With no implications to the political leanings of the singers, themselves, Sousa demonstrated, not only his intellectual capacity, but his dry wit, when he later remarked about having been kissed by both sides, a Bohemian and a Japanese, and that neutrality had been vindicated, and there was now, no need for any more. Sousa, who had been happily married for thirty-six years, had celebrated his anniversary on December 30, about ten days before, jokingly declared, if this keeps up, he will have to start wearing a muzzle.